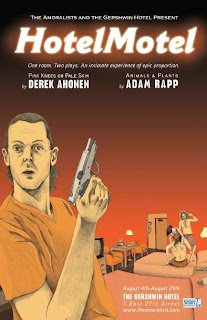

HotelMotel

Site-specific theatre rocks! HotelMotel is a double-feature presented by The Amoralists and the Gershwin Hotel, with both plays running in a small back room at the Gershwin Hotel. There’s only room for 20 audience members; we are never more than a yard or two from the cast and set (sometimes, we’re thisclose to both); and the experience envelops you the moment you walk in and doesn’t let you go until you exit the hotel and head back out on the streets of Manhattan. (Actually, the experience will likely stay with you longer than that...)

Site-specific theatre rocks! HotelMotel is a double-feature presented by The Amoralists and the Gershwin Hotel, with both plays running in a small back room at the Gershwin Hotel. There’s only room for 20 audience members; we are never more than a yard or two from the cast and set (sometimes, we’re thisclose to both); and the experience envelops you the moment you walk in and doesn’t let you go until you exit the hotel and head back out on the streets of Manhattan. (Actually, the experience will likely stay with you longer than that...)

(I won’t give away too many of the experiential details because I found it fun to be surprised by them. I will tell you this, though: Usually, I’m really adamant about having my personal space in my seat. I almost always try to sit in an aisle seat so that if the person next to me is unintentionally spilling over into my space (or the person is just rude and thinks he can spread his legs as far as he wants, inconsiderate of the presence of my leg), I can stretch myself out into the aisle. For the first play in HotelMotel, Derek Ahonen’s Pink Knees on Pale Skin, the small seats are set up so close that not only are the seats touching, but audience members are, as well. Under normal circumstances, this would annoy me to no end. But here, I loved it. It was all part of the intimate experience; all part of exploring intimate details with strangers and allowing yourself to be vulnerable to whatever lies ahead. The seats were rearranged for Adam Rapp’s Animals and Plants. Audience members weren’t as close to each other, but we were even closer to – in fact, part of – the action.)

We begin with Pink Knees. This frank work truly explores the human condition. As diabolical, disturbing or disconcerting as some characters and situations were, in Pink Knees, Ahonen (who also directs his play) presents some of the most raw, real and fully-developed characters and discussions about love and sex I have ever encountered. (And the fearless cast, led by Amoralist Acting Company member Sarah Lemp, contributed greatly to the verisimilitude. They had to – we were literally right under their noses!) Pink Knees, construction-wise, has the qualities of a well-made play: it takes place in one location and in real time. It also has the qualities of a well-executed play, which are often indefinable but, like obscenity, I know it when I see it. And I saw it in Pink Knees.

We begin with Pink Knees. This frank work truly explores the human condition. As diabolical, disturbing or disconcerting as some characters and situations were, in Pink Knees, Ahonen (who also directs his play) presents some of the most raw, real and fully-developed characters and discussions about love and sex I have ever encountered. (And the fearless cast, led by Amoralist Acting Company member Sarah Lemp, contributed greatly to the verisimilitude. They had to – we were literally right under their noses!) Pink Knees, construction-wise, has the qualities of a well-made play: it takes place in one location and in real time. It also has the qualities of a well-executed play, which are often indefinable but, like obscenity, I know it when I see it. And I saw it in Pink Knees.

This is not for the prudish or unadventurous, but if you fall outside of those two categories and can snag a ticket to HotelMotel, what you’ll see in Pink Knees is an unhinged (though completely in control) doctor, Sarah Bauer (Sarah Lemp), who counsels couples in crisis through her own brand of sex-orgy therapy. That probably sounds more salacious than it is. It’s really a character study with sexual elements. One woman learns to enjoy sex; one man pleads for forgiveness; and a young man see his mother’s true colors and has a twisted reaction.

This is not for the prudish or unadventurous, but if you fall outside of those two categories and can snag a ticket to HotelMotel, what you’ll see in Pink Knees is an unhinged (though completely in control) doctor, Sarah Bauer (Sarah Lemp), who counsels couples in crisis through her own brand of sex-orgy therapy. That probably sounds more salacious than it is. It’s really a character study with sexual elements. One woman learns to enjoy sex; one man pleads for forgiveness; and a young man see his mother’s true colors and has a twisted reaction.

In his program notes for the play, playwright and director Ahonen writes that his parents and grandmother were always begging him “never to get married. My grandmother’s reasoning was that a spouse will take away your family. My father’s was that a spouse will take away your dreams. My mother’s was that a spouse will take away your youth.” It easy to see the manifestations of this wisdom(?) in Ahonen’s characters, but it’s also easy to see that he’s simply exploring some fundamental underpinnings of relationships.

Relationships are difficult; they’re messy; they’re complicated; they’re heart wrenching. They can also be deeply satisfying, enlightening and joyful, but audience members should consider themselves lucky that Ahonen leaves that aspect to romantic comedies (which are often neither romantic nor comedic). It is refreshing and not just a little reassuring to have a bold, brave and provocative voice speaking up for the less-explored side of human connection.

Relationships are difficult; they’re messy; they’re complicated; they’re heart wrenching. They can also be deeply satisfying, enlightening and joyful, but audience members should consider themselves lucky that Ahonen leaves that aspect to romantic comedies (which are often neither romantic nor comedic). It is refreshing and not just a little reassuring to have a bold, brave and provocative voice speaking up for the less-explored side of human connection.

And now on to Animals and Plants, an Adam Rapp play that starts off very funny and spirals out into a dark meditation on loyalty and testing the limits of humanity. (As he’s been doing lately, Rapp directs his own work here.)

We’re in a motel room in Boone, North Carolina, and two drug runners are hanging out before the big score. It is snowing outside, as it has been for 17 hours. Dantly (William Apps) is sitting listless on the bed. He is a typical young, Adam Rapp-character, which is to say he’s sweet but simple. He needs protecting. Burris, Matthew Pilieci, has energy (and words) to spare as he bounces around the room, finishing up his post-shower routine and engaging in some calisthenics. He’s all braggadocio, but at the moment he is protective of Dantly.

We’re in a motel room in Boone, North Carolina, and two drug runners are hanging out before the big score. It is snowing outside, as it has been for 17 hours. Dantly (William Apps) is sitting listless on the bed. He is a typical young, Adam Rapp-character, which is to say he’s sweet but simple. He needs protecting. Burris, Matthew Pilieci, has energy (and words) to spare as he bounces around the room, finishing up his post-shower routine and engaging in some calisthenics. He’s all braggadocio, but at the moment he is protective of Dantly.

In the opening scene, Rapp once again shows off his flair for the seemingly mundane but spot-on conversations that take place when nothing is happening. He has a knack for writing in his characters’ voices, not his own, and capturing exchanges that happen in the intimacy of closed quarters. (I was reminded – by the craft of the conversation, not its content – of the dialogue that opened Rapp’s Welcome Home Dean Charbonneau.)

In the opening scene, Rapp once again shows off his flair for the seemingly mundane but spot-on conversations that take place when nothing is happening. He has a knack for writing in his characters’ voices, not his own, and capturing exchanges that happen in the intimacy of closed quarters. (I was reminded – by the craft of the conversation, not its content – of the dialogue that opened Rapp’s Welcome Home Dean Charbonneau.)

Soon, though, Burris leaves and Dantly is momentarily alone with his all too vivid dreams. He wakes up to find Cassandra (who just might be very aptly named), the clerk from the head shop he had taken a shine to. Dantly is looking for a connection and he thinks he may have found it in Cassandra (Katie Broad). When he discovers that Cassandra may not bring hope but something far darker (like, perhaps, Buck (Brian Mendes)), and that he’s been betrayed, he reacts with violence and must retreat to something pure and true, like the snow.

Rapp writes in his program notes of the characters, “I hope your proximity to them will inspire you to want to reach out and touch them, take them in your arms, curse them or cover your eyes while peaking through the gaps in your fingers.” Indeed, at various moments I wanted to do all those things. I was completely transfixed. I found the more surreal moments a little more difficult to sit through than the more naturalistic moments, but taken as a whole it worked. The naturalistic moments wouldn’t have made sense without the vivid personification of dreams.

Rapp writes in his program notes of the characters, “I hope your proximity to them will inspire you to want to reach out and touch them, take them in your arms, curse them or cover your eyes while peaking through the gaps in your fingers.” Indeed, at various moments I wanted to do all those things. I was completely transfixed. I found the more surreal moments a little more difficult to sit through than the more naturalistic moments, but taken as a whole it worked. The naturalistic moments wouldn’t have made sense without the vivid personification of dreams.

And that's the thing about the the specificity of the site and the closeness and intimacy of the environment. If this was in a slightly larger, more traditional theatre with a proscenium stage, I would have been able to look away; I would know I'm in a theatre instead of being immersed in this world. I needed to be immersed in this world in order to go on this strange journey with Dantly - in order to sympathize with him I had to really experience his circumstances. That's the awkward, beautiful, unique thing about site-specific theatre, and it rocks.

And that's the thing about the the specificity of the site and the closeness and intimacy of the environment. If this was in a slightly larger, more traditional theatre with a proscenium stage, I would have been able to look away; I would know I'm in a theatre instead of being immersed in this world. I needed to be immersed in this world in order to go on this strange journey with Dantly - in order to sympathize with him I had to really experience his circumstances. That's the awkward, beautiful, unique thing about site-specific theatre, and it rocks.

For more information, visit theamoralists.com. HotelMotel runs through August 29.

Production stills taken by Monica Simoes.

Comments

Post a Comment