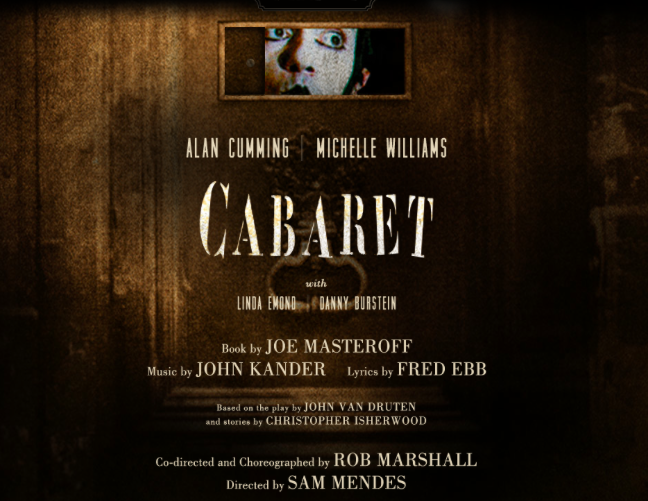

Cabaret

Willkommen back, dear readers! In a rare occurrence, Broadway audiences are being treated to a return engagement of a wonderfully successful revival. Opening at Roundabout's Studio 54 in March 1998, the Sam Mendes–Rob Marshall production of Cabaret brought Emcee Alan Cumming stateside, earning the Scottish star a Tony Award and catapulting him to fame. (He can currently be seen on The Good Wife, and he was last seen on Broadway in Macbeth.) The revival continued through 2004 (I saw it in 2001, when Cumming and Natasha Richardson (as Sally Bowles) had long since left the production), giving Neil Patrick Harris, Michael C. Hall, John Stamos, Norbert Leo Butz and a slew of other top actors an opportunity to welcome people to the Kit Kat Club. But in the 10 years since its closing, audiences have not had the chance to enter said club and enjoy a cabaret.

I'm usually wary of revivals. There are so many talented writers out there, and while a revival might be a safer choice financially, they can also stifle the creativity of less bankable but not at all less credible or worthy voices. The way I see it, revivals should pop up only if they are undeniably relevant (like Hair in 2008/2009) or if the perfect storm forms and you have the right cast and right director to make the revival too much fun to pass up (like Anything Goes in 2011). This return engagement of the John Kander–Fred Ebb 1966 classic is both.

With its depiction of Berlin in 1930, political turmoil abounds—national identity, the persecution of a minority, charismatic but dangerous leaders coming into power—making it all too relevant to today's landscape. And with no disrespect meant to Joel Grey (who originated the role of the Emcee in Cabaret's Broadway debut), I feel like watching Alan Cumming as the Emcee is like watching Lord Chamberlain's Men perform Shakespeare. (Or maybe like watching Mark Rylance perform Shakespeare, which he did so winningly earlier this season.)

With its depiction of Berlin in 1930, political turmoil abounds—national identity, the persecution of a minority, charismatic but dangerous leaders coming into power—making it all too relevant to today's landscape. And with no disrespect meant to Joel Grey (who originated the role of the Emcee in Cabaret's Broadway debut), I feel like watching Alan Cumming as the Emcee is like watching Lord Chamberlain's Men perform Shakespeare. (Or maybe like watching Mark Rylance perform Shakespeare, which he did so winningly earlier this season.)Cabaret (which features a book by Joe Masteroff) is also important to today's musical theatre zeitgeist. The gritty, unflinching musical came to light during a period when musicals were getting a little heavier, and returns now, when the most successful and popular musicals are glossy, poppy and barely skin deep. It's traditional in its structure, using the show-within-a-show device to help audiences believe people would just burst into song, but still rather disarming in the way those songs and musical numbers reveal depth of character; they catch you off-guard with their candor and bite, which is what this musical theatre acolyte relishes in a score.

Some of the most moving musical moments in this iteration come courtesy of Michelle Williams (Blue Valentine, Shutter Island), who makes her Broadway debut as Sally Bowles, "a most talented young lady from England," the nightclub chanteuse who is challenged to live in reality when she meets American writer Cliff (a great Bill Heck).

Over the years, I've been turned off by Williams's public persona. She always seems to be crawling into herself, batting her eyelashes like a Kewpie doll, and pouting or making a duck face. But every time I see her in something, I'm reminded that I need to separate my perception of her public persona from her talent, because this lady is good at what she does.

Williams thoroughly impresses as Sally, a role made iconic by Liza Minnelli. (Ms. Minnelli didn't originate the role on Broadway, but she starred in the film and several Sally songs became a permanent part of her repertoire, as captured in her Liza with a Z special.) The singing actress appears natural and comfortable on stage, a welcome change as compared to many other film actors making their Broadway debut. (It should be noted that this is not Ms. Williams's stage debut though it marks the first time she's appeared on Broadway.) Looking at her body of work, it's easy to see that Williams is a fearless actress, which, I think, is what helps her rendition of "Maybe This Time" to be truly affecting and her "Cabaret" to be captivatingly powerful.

Williams thoroughly impresses as Sally, a role made iconic by Liza Minnelli. (Ms. Minnelli didn't originate the role on Broadway, but she starred in the film and several Sally songs became a permanent part of her repertoire, as captured in her Liza with a Z special.) The singing actress appears natural and comfortable on stage, a welcome change as compared to many other film actors making their Broadway debut. (It should be noted that this is not Ms. Williams's stage debut though it marks the first time she's appeared on Broadway.) Looking at her body of work, it's easy to see that Williams is a fearless actress, which, I think, is what helps her rendition of "Maybe This Time" to be truly affecting and her "Cabaret" to be captivatingly powerful.As in 1998, The Kit Kat Club takes over Studio 54. The traditional orchestra seats have been removed and replaced with cabaret-style seating (tables and chairs and table-top lamps); such seating spills into the front mezzanine, as well. The lights and flash of the cabaret world even make their way into the rear mezzanine, so everyone, even those poor people (called out as such by the Emcee) who, like me, sit the way way back, can be part of the experience. (Scenic design is by Robert Brill; lighting design is by Peggy Eisenhauer and Mike Baldassari. Tony winner William Ivey Long designed the costumes.)

I can't conclude my review of Cabaret without mentioning beloved stage veterans Linda Emond (The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide..., Death of a Salesman) and Danny Burstein (The Snow Geese, Follies). The two Tony nominees are simply terrific as Fraulein Schneider and Herr Schultz, respectively. Their chemistry and zeal in the first act makes their parting in the second that much more sorrowful. Placing them on stage together in these roles is nothing short of perfect casting.

I can't conclude my review of Cabaret without mentioning beloved stage veterans Linda Emond (The Intelligent Homosexual's Guide..., Death of a Salesman) and Danny Burstein (The Snow Geese, Follies). The two Tony nominees are simply terrific as Fraulein Schneider and Herr Schultz, respectively. Their chemistry and zeal in the first act makes their parting in the second that much more sorrowful. Placing them on stage together in these roles is nothing short of perfect casting.So leave your troubles outside, and let the Emcee entreat you back to the Kit Kat Club, where they have no troubles and where life—and this production—is beautiful.

For more information and to purchase tickets to Cabaret, visit cabaretmusical.com. (Young adult theatergoers: this is a Roundabout production so get your Hiptix!)

Comments

Post a Comment